The 6 fundamentals for being data-informed PM

6 Key things to know before talking about “metrics” as a PM

6 Key things to know before talking about “metrics” as a PM

Product Managers often find themselves navigating the complex world of metrics and data analysis. It can seem overwhelming, with numerous terms and concepts to understand.

This article aims to be your guiding light on some key terms about metrics to be “data-informed”. These 6 fundamentals helped me understand and use metrics effectively to become a stronger product manager.

Metrics show you the way, not the destination!

Before we talk about Metrics, it’s incredibly important to first define their purpose.

Metrics are not the GOAL! Metrics show you signals to tell you if you’re in the right path or not

I honestly see this misunderstanding of KPIs and metrics in companies a lot leading to prioritizing the wrong thing or mis-understanding the needed path to success.

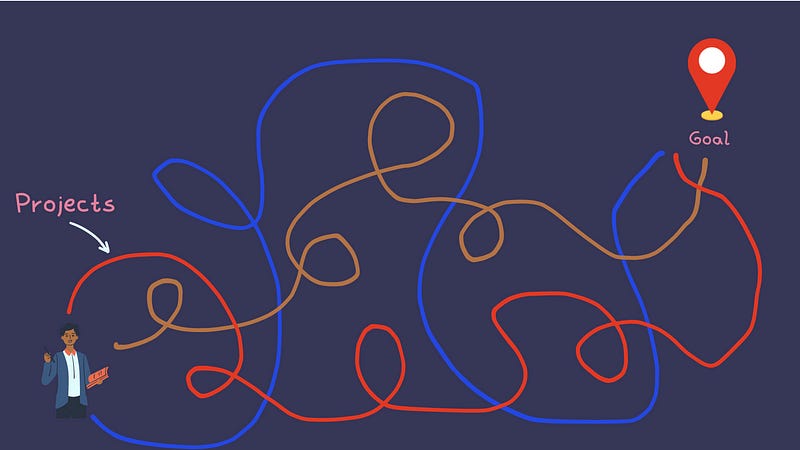

Here’s a simple illustration to easily explain this…

Your GOAL is your destination.

There are several PATHS to get you there. These are projects, experiments, epics, features, strategies, etc. As you see in the pic below, there are many ways to get to where you want to be

But life is not as simple as that. In reality, each road is unique in its obstacles and roadblocks and most importantly, its hidden uncertainties. This is what makes everything we do to reach our goal (building a great product or a company) have some sort of risk. This is why we strategize, prioritize, and plan to mitigate issues and minimize risks.

Now here’s where METRICS comes into the picture. Metrics are the sign roads that tell you whether you’re getting closer or away from your GOAL.

I see a lot of companies or leaders talking about KPIs as if they’re the destination. Also, metrics can sometimes be unique to the Project (aka the road) you decide to take leading to the goal. It’s highly related to the path (which is an assumption and can change), not the destination. Especially in early-stage startups, when most of the Projects are powered by a lot of intuition, those metrics become flexible

With this in mind, I’d love to share 6 lessons I learned about metrics that I believe will make you a stronger PM when having any metric or KPI-related dialogs.

1) OMTM & Associated metrics

Always understand the difference and even help define it in your company if it’s not clear.

OMTM stands for Only Metrics That Matter and are the metrics you want to focus on to get to your goals (not your project metrics). It’s mainly the most important metric for your stage to reach your Target.

Usually, you should have an OMTM for your solution (not the product). These are heavily related to your ultimate Value Prop, promise, and the ultimate outcome you eventually want to help your customer reach. It’s purely related to your solution, not your product!

I can write another post about solution vs. product but here’s a quick distinction. Your solution is a promise, a value proposition, and the “WHAT” you want to do to your customer. The product is the HOW. It’s the delivery vehicle of that promise.

To be ambitious and build something for the future, your OMTM should be tied to your solution, not your product!

OMTM is important because:

Help you to Focus: One of the keys to startup success is achieving real focus and having the discipline to maintain it. You may succeed if you’re unfocused, but it’ll be by accident. Every industry has KPIs, if you’re a restaurant owner, it’s the number of covers (tables) in a night; if you’re an investor, it’s the return on an investment; if you’re a media website, it’s ad clicks; and so on.

It answers the most important question you have: At the beginning, you’ll be answering a hundred different questions. You need to identify the riskiest areas of your business as quickly as possible, and that’s where the most important question lies. When you know what the right question is, you’ll know what metric to track in order to answer that question. That’s the OMTM

It forces you to draw a line in the sand: After you’ve identified the key problem on which you want to focus and your solution, you need to set goals. You need a way of defining success. You’ll never learn or know when to pivot if you don’t have a clear focused goal.

It focuses on the entire company: Display your OMTM prominently through web dashboards, on TV screens, or in regular emails.

It inspires a culture of experimentation: Experimentation is critical to move through the “build → measure → learn” cycle as quickly and frequently as possible. It will lead to “small- F” failures (learning failures) but will help you avoid “big-F” failures. But you don’t know how or what to experiment with if there’s not one focused goal in mind. When everyone rallies around the OMTM and is given the opportunity to experiment independently to improve it, it’s a powerful force. Picking the OMTM lets you run more focused controlled experiments quickly and compare the results more effectively.

OMTM sometimes is called NSM (north star metrics). I wrote, here, a small post about the key ingredients of NSM.

Supportive (or associated) Metrics, on the other hand, are the metrics that teach you something related to what you want to learn during an experiment towards your OMTM. They change from an experiment to another, a project to another, and for startups, from an MVP to another!

Metrics often come in pairs. Behind them lurks a fundamental metric like revenue, cash flow, or user adoption. Ex, Conversion rate (the percentage of people who buy something) is tied to time-to-purchase (how long it takes someone to buy something). Together, they tell you a lot about your cash flow.

2) Qualitative vs. Quantitative

Qualitative and quantitative metrics both play crucial roles in product management.

Qualitative metrics are derived from methods such as user interviews, focus groups, and user testing. These metrics provide rich, detailed information that helps product managers understand user behaviors, motivations, and feelings. They add context and depth to the numbers, offering insights that quantitative metrics alone may not reveal. While Quanta data tells us the “WHAT”, Quala data tells us the WHY, which is what most of the time leads to innovative solutions.

Quantitative metrics, on the other hand, offer statistical, numerical data that can be measured and analyzed. These metrics, such as user engagement rates, churn rates, and conversion rates, provide hard evidence about what is working in a product and what isn’t. They allow product managers to track progress, measure results, and make data-informed decisions. While Quala data uncovers for us an “aha moment” (a discovery or insight), Quanta data is what validates the size of that (aka proves signal over noise). It’s easy to be dragged to some ideas from a customer interview but you’ll never know whether, on a larger scale, this is actually a good or bad idea

However, the most effective product management often involves a balanced combination of both qualitative and quantitative metrics. While quantitative metrics provide measurable and actionable insights, qualitative metrics offer the “why” behind these numbers. Together, they provide a comprehensive understanding of user behavior and product performance, enabling product managers to make informed, strategic decisions.

A rule of thumb when starting something new is to lead with qualitative data. Initially, you’re looking for qualitative data. You’re exploring. You’re getting out of the building. Quala data is messy, subjective, and imprecise. It’s the stuff of interviews and debates. It’s hard to quantify. You can’t measure qualitative data easily. BUT it uncovers gaps!

3) Vanity vs. Actionable

I see PMs make this mistake often. Vanity metrics are data you cannot act upon, like total signups, and GMV, while Actionable metrics are data that leads to progress, for example, % of active users.

It crushes my heart when we start a status meeting and see a bold number in our status review meetings

“We’re $300k in GMV this month”

My immediate reaction to these statements is: OK… what does this tell us??? So what??? Is this good, bad, average??

Vanity metrics, as the name suggests, are often metrics that look good on paper but don’t necessarily provide real value or insight for a product manager. They are numbers that can easily be manipulated to appear impressive, but they don’t necessarily correlate with the key objectives of your product. As Teresa Torres, a product discovery coach, once said, “Vanity metrics can mislead teams into thinking they are successful when they are not.”

Vanity metrics lack context. Piece of data on which you cannot act upon. You want your data to inform, guide, and improve your business model, to help you decide on a course of action.

Whenever you look at a metric, ask yourself, “What will I do differently based on this information?”

For example, “total signups.” This is a vanity metric. The number can only increase over time (a classic “up and to the right” graph). It tells us nothing about what those users are doing or whether they’re valuable to us. They may have signed up for the application and vanished forever.

“Total active users” is a bit better (assuming that you’ve done a decent job of defining an active user) but it’s still a vanity metric. It will gradually increase over time, too.

Actionable metrics, on the other hand, are the ones that truly matter. They provide insights that can influence decisions, inform strategies, and drive actions. They are directly tied to the goals and objectives of a product, providing real and tangible evidence of progress (or lack thereof). As Marty Cagan, Partner at Silicon Valley Product Group, put it, “The most effective product teams use short, rapid iterations with quantitative testing to constantly assess their progress.”

Actionable metric usually comes in a percentage form like “percent of active users.” When you change something about the product, this metric should change, and if you change it in a good way, it should go up. That means you can experiment, learn, and iterate with it. It becomes even more powerful when you see a long this metric as an indicator or change (like +5% from last month). Now, this becomes informative.

It’s crucial for product managers to not get distracted by shiny vanity metrics and instead focus on the actionable metrics that will truly help them understand and improve their product. As Jeff Gothelf, author of Lean UX, reminds us, “The only metrics that entrepreneurs should invest energy in collecting are those that help them make decisions.” So, always question the value of the numbers in front of you, and stay focused on the ones that help you make informed decisions about your product.

4) Exploratory vs. Reporting data

There are four types of information we have according to Donald Rumsfeld:

Things we know we know (FACTS): Maybe wrong and should be checked against data. However, many gurus will tell you to experimentally validate these types of assumptions. Most of the time, that’s not needed. You can research and gather facts using Google and statistics to prove your point. If it’s faster and not risky, then use Facts.

Things we know we don’t know (QUESTIONS): The “known unknowns” are what needs reporting by asking questions and validating them. It can test our intuitions, turning hypotheses into evidence. I advise every PM to collect a list of Questions (or problems without solutions). Many PMs have backlogs, which is a list of solutions (aka features), but rarely do I see a PM who keeps a list of problems.

Things we don’t know we know (INTUITION): This is what we should quantify and teach to improve effectiveness and efficiency. It can provide the data for our spreadsheets, waterfall charts, and board meetings.

Things we don’t know we don’t know (EXPLORATION): The “unknown unknowns” need exploration to uncover an unfair advantage and interesting epiphanies to validate our biz model and product NSM. It can help us find the nugget of opportunity on which to build a business.

With that being said, Product managers often find themselves in the unique position of having to navigate between exploratory (research data) and reporting (testing data). Both types of data are crucial to the success of a product, but they serve different purposes and require different approaches.

Exploratory data, as the name suggests, is used to explore new ideas, hypotheses, and opportunities. It’s about seeking out the “unknown unknowns,” as former U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld put it. This type of data is often qualitative, gathered through methods like user interviews, focus groups, and field studies. It can provide rich insights about user behavior, needs, and experiences that can inform product strategy and innovation. “Exploratory research is really about discovery,” says Teresa Torres, a product discovery coach. “It’s about going out into the world and learning things you didn’t even know to ask about.”

On the other hand, reporting data, or testing data, is more quantitative. It’s about measuring and analyzing product performance and user behavior. This type of data is often gathered through methods like A/B testing, usability testing, and analytics. It can provide hard evidence about what’s working and not, allowing product managers to make data-informed decisions and iterate on their products. “Testing is all about validation,” says Marty Cagan, Partner at Silicon Valley Product Group. “It’s about taking what you’ve learned through exploratory research, turning it into a tangible product, and then testing it to see if it meets your users’ needs and business objectives.”

In essence, exploratory data helps product managers ask the right questions, and reporting data helps them find the answers. Both are essential in the product management process, and the most effective product managers know how to use both types of data to their advantage. As Jeff Gothelf, author of Lean UX, puts it, “The most effective product teams are those that can balance the need for exploratory research with the rigor of data-driven decision-making.”

5) Leading vs Lagging

These are other metric terminologies that PMs need to know. A leading metric (also known as predictive metrics) tries to predict the future. For example, the current number of prospects in your sales funnel gives you a sense of how many new customers you’ll acquire in the future.

They can help product managers anticipate trends, identify opportunities, and make proactive decisions. For instance, the rate of user sign-ups for a beta version of a product can indicate future user engagement levels. As product leader Martin Eriksson of Mind the Product states, “Leading metrics give you a chance to change the outcome before it’s too late. They deliver foresight and the opportunity to course correct.”

Leading metrics are also considered Input metrics, which usually measure the actions you take that will hopefully lead to results. These can include things like the number of sales calls made or marketing dollars spent. These are within your control. You need a lot of these to measure performance and expect results

On the other hand, a lagging metric (also known as outcome metrics), such as churn (or account cancellation or product returns) gives you an indication that there’s a problem but by the time you’re able to collect the data and identify the problem, it’s too late. The customers who churned out aren’t coming back. That doesn’t mean you can’t act on a lagging metric but it suggests actions based on past performance.

These metrics measure the results of the actions you take (leading action). These can include things like sales revenue or customer acquisition. These are not directly within your control but are influenced by your input metrics.

They are often easier to measure but harder to improve or influence. Examples include churn rates or revenue figures. These metrics are useful for understanding the results of past actions but do not provide insights into future performance. Jeff Gothelf, author of Lean UX, highlights this when he says, “Lagging metrics give us a clear view of our past performance. They’re easy to measure but hard to influence directly.”

In the early days of your startup, you won’t have enough data to know how a current metric relates to one down the road, so measuring lagging metrics at first is expected as they can help provide a solid baseline of performance. However, it’s essential to build leading metrics along your customer journey (along each customer touch point) to understand the whole picture and to be able to influence it.

That’s why striking a balance between leading and lagging metrics is critical for product managers. While leading metrics provide an opportunity to influence future outcomes, lagging metrics help track the success of past initiatives.

6) Correlated (Relative) vs Causal (Absolute)

Sometimes, it's not enough to look at the numbers in isolation. You need to consider how they compare to other metrics or benchmarks. Correlated metrics are those that appear to have a relationship with one another. They’re called relative metrics because they provide context by comparing one figure to another, such as revenue growth percentage or customer retention rate.

Causal metrics, on the other hand, directly result from an action or set of actions. If a change in one variable, such as the introduction of a new feature, leads to a noticeable change in another variable, like an increase in user engagement, this would be a causal relationship. They’re called absolute metrics because they are standalone figures such as total revenue or number of customers. On the other hand,

Causal metrics are harder to identify because they require rigorous testing and the elimination of other potential influences. Marty Cagan, Partner at Silicon Valley Product Group, emphasizes this point by stating, “Causal relationships provide the ‘why’ behind our observations. They allow us to predict outcomes based on our actions, but they require careful, controlled experimentation to validate.”

For example, let’s say you made $1 million in revenue this year. That’s an absolute metric. It’s an impressive figure on its own, but it doesn’t tell you much about your business’s performance. However, if you know that your revenue grew by 20% compared to last year, that’s a relative metric.

It provides context and lets you understand that your business is growing.

Finding a correlation between two metrics is what makes a PM stand out from another. And I can’t emphasize this more, but this is the most “aha moment” for all your managers and leaders. If you can help predict what will happen using correlation analysis and relative metrics, you become incredibly valuable to the company.

After correlation, comes causation. And that’s a whole ball game to play. It’s the gold that every startup or leader seeks because finding the cause of something means you can change it!

Causations aren’t simple one-to-one relationships. Many factors conspire to cause something. So you’ll seldom get a 100% causal relationship. A can correlate with B, but you never know if C is the cause of A & B.

For instance, there may be a correlation between the time users spend on a product and their likelihood to make a purchase. However, correlation does not imply causation, and it’s important to avoid falling into the trap of assuming so. As Teresa Torres, a product discovery coach, warns, “Correlation can point us in the right direction, but it doesn’t tell us what lever to pull.”

You prove causality by finding a correlation, then running an experiment in which you control the other variables and measure the difference. This is hard to do because no two users are identical; it’s often impossible to subject a statistically significant number of people to a properly controlled experiment in the real world.

In the realm of product management, leveraging both correlated and causal metrics is key for a clear understanding of product performance. While correlated metrics may help identify trends and patterns, causal metrics provide the concrete evidence needed to validate product decisions. Together, they form a comprehensive data-driven approach to product management. Jeff Gothelf, author of Lean UX, sums this up beautifully, “The magic is in the mix. By balancing correlation with causation, and relative metrics with absolute ones, product managers can navigate the complex data landscape with confidence.”

So what makes a great metric?

In short, a checklist I always use for metrics includes questions around the following factors:

1) Comparative: Being able to compare a metric to other time periods, groups of users, or competitors helps you understand which way things are moving. “Increased conversion from last week” is more meaningful than “2% conversion.” “number of users acquired over a specific time period”. time or segment comparative.

2) Understandable: If people can’t remember it and discuss it, it’s much harder to turn a change in the data into a change in the culture.

3) Ratio (or Rate): Like an accountant, you need several ratios they look at to understand the health of your startup. They are considered essential because:

Ratios are easier to act on: Think about driving a car. Distance traveled is informational. But speed (distance per hour) is something you can act on, because it tells you about your current state, and whether you need to go faster or slower to get to your destination on time.

Ratios are inherently comparative: If you compare a daily metric to the same metric over a month, you’ll see whether you’re looking at a sudden spike or a long-term trend. In a car, speed is one metric, but speed right now over average speed this hour shows you a lot about whether you’re accelerating or slowing down.

Ratios are also good for comparing factors that are somehow opposed, or for which there’s an inherent tension: In a car, this might be distance covered divided by traffic tickets. The faster you drive, the more distance you cover — but the more tickets you get. This ratio might suggest whether or not you should be breaking the speed limit.

4) Change the way you believe and behave: Most important, what will you do differently based on changes in the metric? Not just a number, but a metric that helps you learn something and act upon it. There should be a change in belief and change in behavior

“Accounting” metrics: (change your belief), like daily sales revenue. When entered into your spreadsheet, they need to make your predictions more accurate. These metrics form the basis of Lean Startup’s innovation accounting, showing you how close you are to an ideal model and whether your actual results are converging on your business plan. Informative but doesn’t tell you what to do, change your belief, not your behavior

“Experimental” metrics: (change your behavior) (or Actionable), Like the results of a test, help you to optimize the product, pricing, or market. Changes in these metrics will significantly change your behavior. Actionable, make you change your behavior. Agree on what that change will be before you collect the data: if the pink website generates more revenue than the alternative, you’re going pink; if more than half your respondents say they won’t pay for a feature, don’t build it; if your curated MVP doesn’t increase order size by 30%, try something else.

Wrapping up…

Being a data-informed product manager involves understanding and utilizing various types of metrics. Metrics are not the goal but signals indicating if the right path is being followed.

Key lessons about metrics include understanding the difference between OMTM and associated metrics, the importance of both qualitative and quantitative metrics, distinguishing between vanity and actionable metrics, the difference between exploratory and reporting data, the use of leading and lagging metrics, and the distinction between correlated and causal metrics.

In the end, a great metric is comparative, understandable, often a ratio, and should change the way you believe and behave!